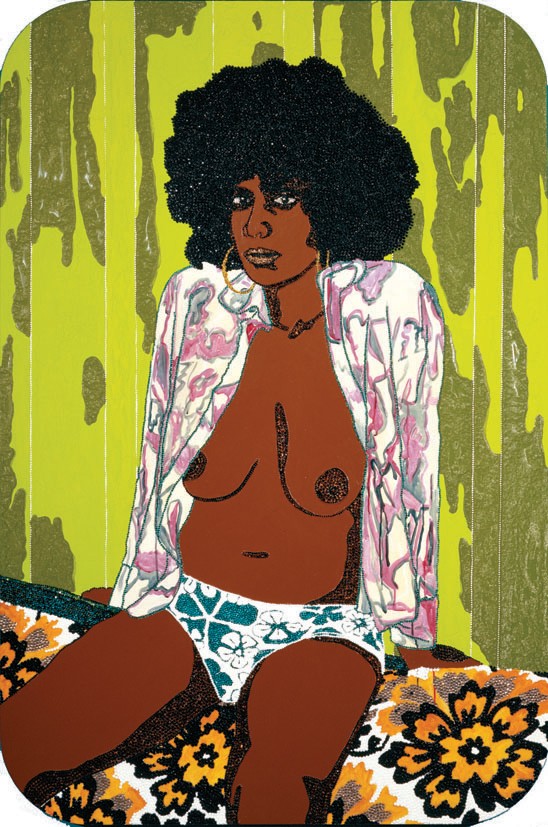

La leçon d’amour, 2008

I first came across Mickalene Thomas’ work on – where else? Pinterest. Because I’m obsessed. Anyway, besides her work being gorgeous and the fact that it focuses on black female identity and sexuality, I was drawn to find out more about her when I discovered that not only is she an openly gay black artist, but she is also from Camden, NJ, where I was born. To top it off, she is now based out of Brooklyn, NY, just as I am.

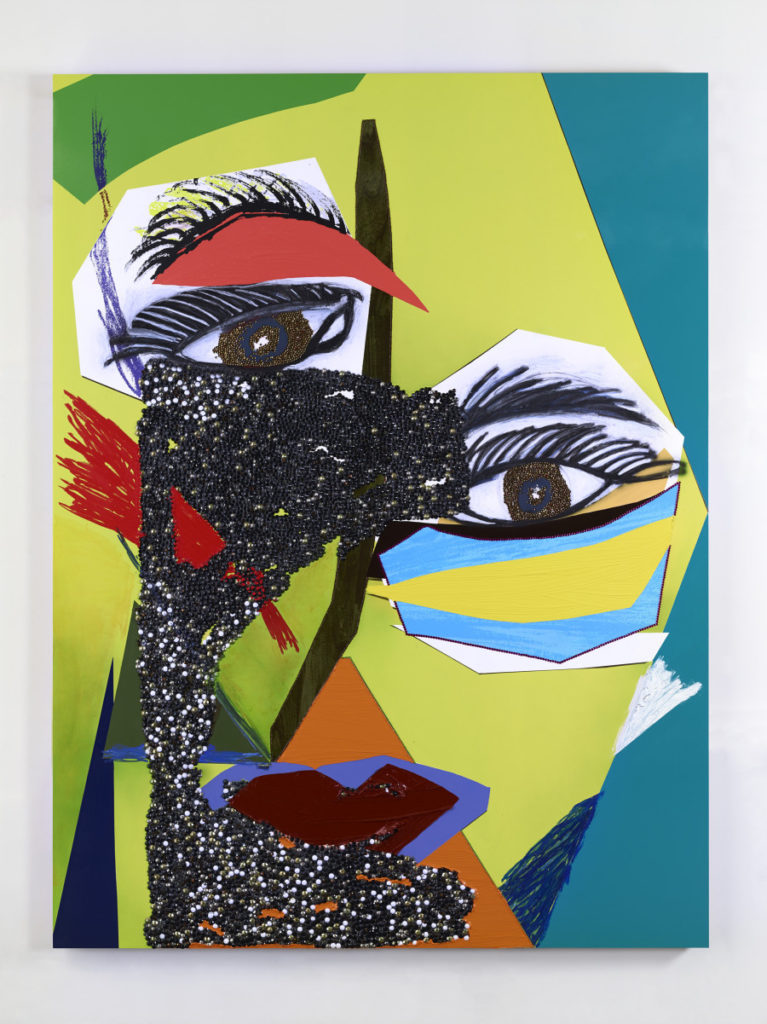

Thomas’ work is a cross between that of Romare Bearden, Henri Matisse’s fauvism, and pop art. She often uses mixed-media, a technique in which she incorporates acrylic paint along with glitter, rhinestones, and other materials. She also utilizes photography and multi-textured collages filled with patterns and bright colors. On her use of patterns, Thomas says in a 2011 interview with PMC Mag that, “Pattern has been an important part of my work for a very long time–I use it to create rhythm and dissonance in the work as well as to reference an array of influences and sources.”

Thomas also creates amazing installations, which are works of three-dimensional creation, often used to transform a space into a representation of a certain concept or theme. Below is Thomas’ “Better Days” installation, which depicts a childhood memory of when her mother hosted parties and other events to raise money to fight causes that affect the Black community.

Remarkably, Thomas introduces the Black woman into classical art in a beautiful and poignant way. This is especially apparent in her 2012 exhibition, “The Origin of the Universe,” where, as Huffington Post puts it, she “…trad[es] in Romantic renditions of milky skin and auburn curls for glamorous black women, their nude forms replaced with bold, printed ensembles, playful wigs, and electric makeup…Thomas does far more than insert black women into an artistic narrative from which they were, for so long, excluded.” With each new exhibit, Thomas challenges societal norms of beauty and forces the viewer to come face to face with how she perceives it.

Even as her work evolves, Thomas continues to put the Black woman at the forefront as she does with the many-layered tapestries and landscapes that surround them. She is able to achieve the fine balance between a Black woman’s sexuality, strength, and femininity and by doing so she allows her work to exude a certain truth and sincerity that is often lacking in the one-dimensional portrayal of the Black woman.

In a 2016 Women in the World, New York Times interview, when asked how her work is affected by how the black woman’s experience is often erased in the feminist dialogue, Thomas says, “By selecting women of color [as my subjects], I am quite literally raising their visibility and inserting their presence into the conversation. I like to think of the portraits as mirrors… We are not validated until we see ourselves, and the mirror is a tangible object that works as an evidence to external appearance. Not only are we present, we demand that we be seen, be heard, and be acknowledged.”

In an Interview Magazine feature, Thomas specifically speaks about the importance of representing the Black woman when it comes to ideals of beauty. She says, “Out of necessity, black women have always had to consider others’ perceptions of a certain beauty ideal, just starting with the skin color.” This is where her art comes in; it not only validates the Black woman’s existence, it seeks to educate the rest of the world on just how beautiful and precious a Black woman’s skin, hair, and body are and that these are not to be devalued by any outsider who may not understand their worth.

In total recognition of her intersectionality, Thomas’ art also conveys powerful messages about the female body and women’s sexuality. Thomas’ “Origin of the Universe” is an invocation of Gustave Courbet’s “Origin of the World” (1866), where Courbet painted a headless torso of a woman with her legs spread, leaving everything for full view. With her rendition, Thomas strips the power away from such a male-centered, controversial work and turns it into something much more empowering. She uses herself as the model, spread legs and all, and in her signature style, she incorporates glitter into the portrait. Thomas makes it her own in such a way that seems to exclaim, ‘It is my body and I will allow you to view it when and how I please!’

Thomas is also adept at seamlessly featuring intimacy between Black women in her artwork. Another piece in her exhibition, “Origin of the Universe”, called “Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires” (also an invocation of Courbet’s work), depicts two Black women with limbs intertwined, taking a nap in the midst of a garden full of disjointed colors and shapes.

Sleep: Deux Femmes Noires, 2012

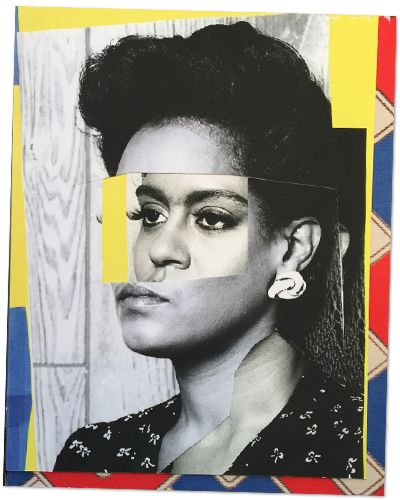

Keeping in theme with intimacy between Black women, Thomas is known for using subjects that she has good relationships with, both working and personal. Her most recent work, “Muse”, is based on a book of the same name and is dedicated to her photography of many of the women she works with. The exhibit and book feature several of Thomas’ personal friends and acquaintances with whom she became closer with as she continued to use them as subjects in her pieces.

Thomas having a relationship outside of the studio with her models allowed for a level of comfort that normally doesn’t exist between the person behind the lens and the person in front of it. But being that some of her subjects were initially her friends, these women were not necessarily professionals. While this gives Thomas’ photographs an endearing, amateurish vibe that all women can relate to, sometimes the women needed to be coached on how to really “give it to the camera.” Thomas explains how she loves the transformative nature of jewelry, clothes, and make-up because they can give a person a certain confidence that they didn’t know they had. She encourages her model friends to feel free in this way when they are in front of her camera.

Thomas having a relationship outside of the studio with her models allowed for a level of comfort that normally doesn’t exist between the person behind the lens and the person in front of it. But being that some of her subjects were initially her friends, these women were not necessarily professionals. While this gives Thomas’ photographs an endearing, amateurish vibe that all women can relate to, sometimes the women needed to be coached on how to really “give it to the camera.” Thomas explains how she loves the transformative nature of jewelry, clothes, and make-up because they can give a person a certain confidence that they didn’t know they had. She encourages her model friends to feel free in this way when they are in front of her camera.

Thomas learned about the power of costume early in her career. One part of the “Muse” exhibit focuses on a performance art piece that Thomas created and starred in during art school. In it, she dressed as different personas to see how people would react. In an interview with Vogue, she says, “It was really about me searching, a discovery of myself, trying to understand some of these stereotypes that were a little mysterious to me, how perception is put onto the black body… Codes and modes of posing and dressing, how those can immediately shift your awareness of how people treat you.” Thomas, who now describes herself as androgynous, remarks on how her classmates did not recognize her in, for example, ultra-feminine attire during the piece. Today, Thomas rejects the idea of singular masculinity or femininity in how she presents herself, saying “I still embody my female self in other ways. And I love that about me. I love vacillating between both of those things, the energy of both.”

I found this particular quote very fascinating because being a woman who is still trying to unlearn patriarchal conventions, the discordance between Thomas’ present androgynous appearance versus the very decidedly feminine nature of her work intrigued me. Thomas says that as a young art student she presented as more feminine and had even modeled for a bit in college so, in the beginning, she used herself as the subject in her art. However, she gradually began removing herself from her work until she was completely absent from it in 2004. With this critical distance, her work, which at the time had only begun to take on an extreme feminine vibe, became even more so and she in turn became more androgynous in her own appearance. She says, “Once I removed myself, I think the work got better… All of my experiences modeling, acting, doing theater, it’s all in the work now. And the work freed me to transform myself.”

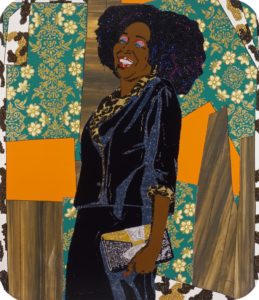

Carla, 2014

How Thomas made it to this open and enlightened point in her life is almost as awe-inspiring as her work itself. I found that her influences are manifold; from her mother to her own life growing up in the 70’s to her appreciation for other visual artists.

Although she studied pre-law and theater arts in college, when she discovered photographer, Carrie Mae Weems’ work, “The Kitchen Table Series” in 1994, she had a change of heart and decided that she wanted to go to art school. Weems’ series awakened a curiosity in Thomas as it addressed topics related to identity and sexuality as a Black woman in the mainstream culture that she had been wrestling with herself. (See video, In Conversation: Mickalene Thomas and Carrie Mae Weems, Brooklyn Museum) After receiving a scholarship based on a series of pastel drawings she created at an art therapy workshop her best friend urged her to go to, she went on to graduate with her Bachelors of Fine Arts from Pratt University in 2000 and she received her Masters of Fine Arts from Yale University in 2002. Throughout her studies, Thomas became extremely well-versed in art history, especially the classics.

Infusing this knowledge of the classics, Thomas created her own style which had more modern themes and genres. For example, much of Thomas’ work brings to mind a 70’s aesthetic, inspired by her childhood growing up in that colorful, glittering decade. The women in her paintings often have lush afros, sequined dresses and pantsuits, and big sparkly earrings. The decor in the rooms that they sit in are equally lavishly adorned.

Thomas is also influenced by African photography, especially Malian photographer Malick Sidebé and South African lesbian photographer, Zanele Muholi who both use population-specific portraiture, infused with notes of art-as-activism, themes that, although are sometimes subtly overshadowed by other layers, Thomas uses in her work. Never straying far from her own style, Thomas will often embellish her photography with her mixed-media techniques. And she not only recreates classic artists’ work, she often recreates her own photographs with collages.

.

Another important influence for Thomas is her wife, Carmen McLeod, who is also an artist. They were married in 2009 and have a daughter. Thomas says, “We have a very close relationship that extends into our studios and a serious critical dialogue. It’s funny though, we didn’t realize just how much we extend into one another’s work until we…realized that she had included five portraits of me in her show and that I had included my first portraits of her in my show!”

Last but certainly not least, Thomas’ mother, former fashion model Sandra Bush, is known as her number one muse, her biggest influence, and has served as the focus of much of her work. Despite having admiration and love for her mother, Thomas admits that because of her mother, her exposure to the fashion industry throughout her childhood and adolescence affected her ideals of beauty from a young age and she was forced to contend with that. Even though this was a source of internal conflict for Thomas’, her mother taught her about confidence as it relates to beauty. She was effortlessly feminine in the way she carried herself and, most importantly, she preached self-love and acceptance.

Thomas’ internal struggle with beauty and femininity continued although she did find herself following in her mother’s footsteps when she dabbled in the modeling industry herself. Because of this discord, her mother’s struggle with drug addiction when Thomas was growing up, and Thomas’ coming to terms with her sexuality and reconciling that with her mother, she and her mother had a strained relationship until Thomas was an adult.

But she tells Huffington Post that her mother became her muse after she was encouraged by her graduate school photography teacher to use her art to try to forge a relationship with her. So Thomas approached her mother to photograph her as the iconic Pam Grier, who they both found to be a captivating, strong, Black woman, and to her surprise, she gladly agreed. Thomas said this experience connected them as not just mother and daughter but as friends and as women. In the Women in the World interview, Thomas says, “…working with her as a model really helped me to understand how her charisma related to me, to my own femininity.”

In spite of their differences in the past, Thomas and her mother were able to repair the relationship through creativity and shared interests. Thomas ended up directing a lovely tribute to her mother right before she died in 2012, “Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman,” which aired on HBO in 2014.

HBO trailer for Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman:

Over the years, Thomas has received many prizes, awards, and grants and is being represented by several studios across the country as well as one in Paris, France. She even completed an artist’s residency in 2011 in Claude Monet’s home and gardens in Giverny, France. Her work has been featured at the MoMA, the Brooklyn Museum, the Smithsonian, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, among others. She has also been given the opportunity to create for magazines and album covers, she and her work have been featured in TV and movies, and she created the first official portrait of Michelle Obama.

Not only do I get goosebumps when viewing Mickalene Thomas’ work but I’m also very inspired by her. In interviews, even with mainstream media, she unapologetically speaks about how her work relates to blackness, womanhood, and sexual identity. She possesses so much talent that the respect that talent demands from the art community allows her the space to talk so freely. I admire her for this as well as her ability to stay true to herself and continue to be so flawlessly superb at her craft. Learning about how she switched her career path from law to the much less traditional field of visual arts shows me that my own transition into the creative world is possible too. Just like her multifaceted paintings, Mickalene Thomas’ life and work serve as a multi-dimensional reminder that as a Black woman, I can feel free to explore the many layers of myself.

Follow Mickalene Thomas and her work on Artsy.com