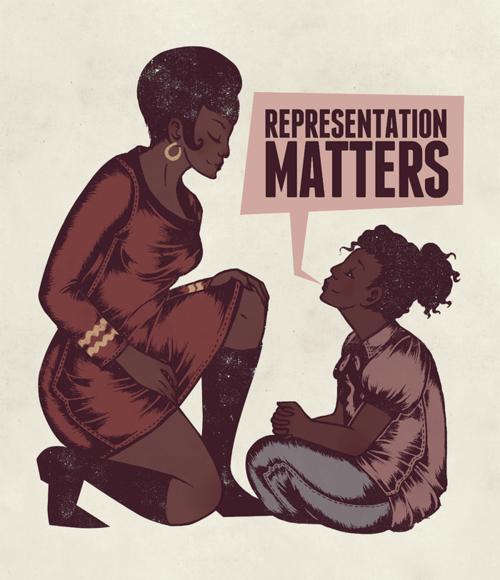

Just like the Black family, Black women have had a similar struggle to be represented positively and accurately on TV. It’s important that Black women are not only given more roles but that these roles are accurate and positive, thereby making them for us, not just about us.

But throughout the years, it has seemed like too much to ask to see TV shows that were both about Black women and also made for Black women. Black women have been awkwardly inserted into TV shows as the token on mostly white shows or as incidental characters on shows with Black ensemble casts (e.g. if the star of the show is a Black man, he will most likely have to have a Black girlfriend, wife, mother, etc.) These characters don’t always necessarily speak to our real experiences as Black women and that is usually not the purpose that they were created for.

I believe that for these shows and characters to be not only about us as Black women, but for us, the shows must be created by Black women, or at least feature our writing or direction so that we can have more control over how we are portrayed. Then we can create characters that exemplify attainable #BlackGirlMagic as well as the relatable girl-next-door persona. We don’t need any more characters who represent the gamut of negative stereotypes; from being fetishized to being the best friend with no love life to being the angry Black woman. In addition, it’s important to note that depending on the era, the face of the Black woman and how we want to be portrayed on television changes.

The Beginnings of Positive Representation of Black Women on TV

To start a discussion about Black women on television, we must acknowledge the first image of a Black woman on TV that was not in a subservient or over-sexualized role. (Note: the very first sitcom to star a Black woman, Beulah [1950-1953], was highly criticized for enforcing caricaturistic stereotypes of Black women). In 1968, Diahann Carroll starred in Julia, the first American sitcom to feature a Black woman in a non-stereotypical role. She played a middle-class nurse who was raising her young son alone after her pilot husband was killed in Vietnam. Although it broke many barriers, it was the source of a lot of controversy. Some people said it was unrelatable and that Julia lived in a world that was unrecognizable to most Black people in America at that time. The show was also criticized for the lack of a Black male figure and people speculated that this was done on purpose to make the show more palpable to white audiences.

Aside from the amazing Black women who were co-stars in the groundbreaking family sitcoms like Good Times and The Jeffersons, after Julia, there were very few shows that featured Black women over the next ten years.

The Black Woman as Token on TV

In the 80’s Black women gradually became more visible in mainstream media but not as the star of the show. They were shown as the sassy sidekick, the co-worker, or the nemesis in all or mostly White casts. These shows did put us on the screen but it wasn’t in a necessarily positive way. The characters were not made for us, by us, or about us. For example, Kim Fields played Tootie on The Facts of Life (1979-1988). Her character was the only Black girl out of four girls who lived with their boarding school house mother, Mrs. Garrett. In the show, Tootie’s race was barely acknowledged and when it was it was not handled very well. In what was probably an earnest attempt to have Tootie confront issues of her race, during one episode in Season 2, she was given a Black love interest who criticized her for only having White friends. By the end of the episode, after calling a meeting with all the other Black girls in the school (who were nonexistent before this episode and only show up once in a later episode), Tootie learns that just because she only has White friends doesn’t mean she has lost her Black identity. From this point on, more Black characters appear but they are Tootie’s relatives or her contrived love interests. These story lines seemed to be a response to backlash the show must have received regarding inclusion in the show. But it is apparent that the writers were not well-versed on exactly how to deal with or accomplish this inclusion.

Then in the early 90’s, Lark Voorhies played Lisa Turtle, the only Black student in the main cast of Saved By the Bell (1989-1992) and Vanessa A. Williams played Rhonda Blair, the only Black tenant in the complex in Melrose Place (1992-1993). These shows treated the Black female characters’ race as a non-existent factor. Looking back, it’s clear that race did have a part to play in these character’s lives, it just wasn’t acknowledged.

Although both women were attractive, successful, and eligible, they never had a successful love interest while their white co-stars had plenty. These are examples of how the opposite of fetishization began to happen with Black female characters in the 1990’s. Black female characters were desexualized and viewed as unwanted, despite them being just as worthy as their white counterparts. But instead of the women lamenting over their invisible love life, the characters thrived despite the show treating them as undesirable. This was the beginning of the strong Black woman trope where Black women grow stronger from adversity and they excel in all things but love, but are somehow better for it. This is clearly not a realistic portrayal of a Black woman or any woman for that matter. But it is not simply because of how the characters’ lack of a love life didn’t seem to affect them – because obviously, a relationship doesn’t mean a successful life. But it is the fact that these Black women were not given the same commodity that most television shows are built upon – love; the commodity that white women are given in droves.

Not acknowledging a character’s race or sexuality made it easier for shows in the 90’s to have a token Black female character without being accused of enforcing stereotypes and without having to put in the work to write a genuine Black character. It is almost impossible for Black women to fully relate to these types of characters since in real life Black women’s race rarely ever goes unnoticed. Black women live with the effects of how their race makes others treat them and how they are expected to behave. In reality, our Blackness cannot be hidden or ignored and, for most of us, we don’t want it to be.

Some show creators did become a little more comfortable with dealing with the race of their Black female characters. On Boy Meets World (1993-2000), Trina McGee played Angela Moore, the main character’s best friend’s on-again-off-again girlfriend and the only Black character on the show. When her race was addressed, it was only as comic relief and although she and Shawn were in an interracial relationship that would have been something to talk about in real life in the 90’s, the show never discussed it. In this instance, the Black female character did get love but the show writers were still unable to address race in a meaningful way.

Then, in 1998 Tangi Miller played Elena Tyler, a central character and the main character’s enemy-turned-friend on Felicity (1998-2002). Elena was the only Black female character and she exemplified both the Black best friend and the strong Black woman tropes. She was tough, opinionated, super serious about her studies, from the city, and attending the college on a scholarship. But, as problematic as this portrayal was, the writers gave Elena a lot of screentime and storylines, even asking her what music she wanted to be played during her scenes. I remember really appreciating Elena’s character and, because it was the early 2000’s when I was just happy to see a face like mine on a mainstream TV show, I don’t think I noticed the tropism. But it was obvious that Elena was simply a token – just one with a more developed character.

The Black Woman in “Equalized” TV Roles

There were a few mostly White-casted shows where Black women were able to leave their mark in a significant way and be more than just a token. Nichelle Nichols played Nyota Uhura on Star Trek (1966-1969). She was encouraged by Martin Luther King, Jr. himself to continue to play the “equal role” instead of quitting the show to go back to musical theater, as she had planned to do. He told her that, “her character signified a future of greater racial harmony and cooperation… ‘You are our image of where we’re going… you are our inspiration… Don’t you understand for the first time we’re seen as we should be seen. You don’t have a black role. You have an equal role.’”

Although race was not discussed on Star Trek, this was not a detriment to the Black community at that time. For one, the show was set in the future, when some may hope that race isn’t as big of an issue as it is today and secondly, the show aired during the Civil Rights Movement, a time where the entire Black population had to fight for equal rights in their everyday lives. Seeing a Black person on TV in a regular role that could have been played by anyone was more than a victory at that time. The show even went on to display the first interracial kiss on television.

On Dynasty, from 1984-1987, Diahann Carroll again changed history when she played Dominique Deveraux, a role that she asked Aaron Spelling for because she believed it was time for the show to become integrated. She told him she wanted to be just like the other female characters on the show, “ridiculous, beautiful, and rich,” but a Black woman. This was something that had never been done on television before and what she called TV’s “first Black bitch,” not the docile characters people were accustomed to seeing Black women play at that time. She remarked that, “‘It was a caricature. No real people were involved in those shows.’ She also wanted to erase stereotypes when it came to playing Deveraux. ‘I told the writers forget that I’m female, forget that I’m black and write it exactly how you would want a rich white man to be and you’ll have it, that’s her.’” In the past, we as Black women had to demand to have powerful Black female characters on TV; the portrayal of the strong black woman was needed in certain eras of oppression. But as TV became more integrated, this character type was exaggerated and overdone to the point of it becoming just another caricature like those before it that we had to work hard to escape. But back in Dynasty days, the “Black bitch” was revolutionary.

Both Nyota Uhura and Dominique Deveraux’s characters equalized Black women, something that was necessary during both shows’ eras. While equalization is important, it is just as important for shows to address racial difference and what that means in society so that characters are more true to life and relatable, something that was also missing in the mostly white 90’s shows mentioned above.

Black Women in Black Ensemble Casts on TV

Often, the only time race is addressed in a relatable way is when a show has an all Black cast. In the late 80’s, early 90’s, more shows with all Black ensemble casts were created and they included great Black female characters. Because these shows had an all Black cast, Black people were equalized, showing that we can have normal lives and storylines like white people can. They made us equal while simultaneously addressing being Black because they were created for Black audiences, by Black producers, writers, and directors. The female characters, although not always the stars of the show, were given enough screen time and dialogue to show depth and a solid backstory, something that was usually not done on white shows. Leading ladies Tisha Martin-Campbell as Gina and Tichina Arnold as Pam in Martin (1992-1997), Garcelle Beauvais as Fancy in The Jamie Foxx Show (1996-2001), and Wendy Raquel Robinson as Regina Greer in The Steve Harvey Show (1996-2002) all did their best to make their marks on their respective male-dominated shows. But in these three shows, and other Black male-centered sitcoms, the focus was the star of the show, the male comedian. The female costar usually was a support to the male character and her role was usually based upon the direction the show was to take based upon the main male character.

Thankfully, there were shows produced by women and therefore had a focus that was a bit more equally balanced between male and female characters like A Different World (1987-1993). After the first season, it was produced by Debbie Allen and starred, alongside the men, Jasmine Guy, Cree Summer, Charnele Brown, and the other female actors. This show addressed many issues dealing with race, gender, and class under the setting of a college campus. The women of the show had just as much importance as the men and all of the characters were well-developed.

But as great as this show was, it was not centered on Black women, but Black men and women as a community. There is nothing wrong with that but with men as costar characters, there’s always the need to find a balance between the positive portrayal of Black men and the positive portrayal of Black women. With already low resources that must split to achieve this goal, it results in a less focused attempt to make Black women a priority.

However, in 1993, a show premiered that was 100% for Black women, about Black women, and created by a Black woman. Living Single was created by Yvette Lee Bowser, making her the first Black woman to develop her own primetime series. It starred Queen Latifah, Kim Fields, Kim Coles, and Erika Alexander who played four Black women friends who lived in a brownstone apartment in Brooklyn, NY. They each had careers, from attorney to receptionist to business-owner to boutique-buyer, in-depth storylines, and unique personalities that were properly explored. They had love lives that didn’t define them and their friendship took the many turns that friendships in real life take. The characters showed a range of emotions and experienced a variety of life situations that made them highly relatable. These women were Black and unapologetic, but they were also human beings with lives like the rest of us, no matter what race. This dynamic was never before seen on TV and Living Single became one of the most popular Black sitcoms of the time. The show lasted until 1998 and when it ended, it left a huge void in TV for the responsible portrayal of the Black woman.

Then in 2000, Mara Brock Akil created the show Girlfriends. It was another show about four Black girlfriends from different backgrounds and showcased their depth of character. Girlfriends, set in California, became the longest running live-action comedy on network television and was dubbed the “Black Sex in the City”. It can be argued that the four characters were a bit “tropie”. For example, Maya was the sassy Black girl, who in the early seasons was caricatured as the “hood chick.” Toni was the Black, bougie bitch with colorism issues. Lynn was the free-spirited, biracial, adopted, bohemian girl, who didn’t accept her Blackness until college. And Joan was the mother hen who brought them all together. But the fact that there was a show on TV that again featured the various lives of Black women was much appreciated. It was created by a Black woman and for Black women audiences. After its long run, it abruptly ended in 2008 due to the writer’s strike and the next time we get to see a group of Black female “friends” is on reality TV.

The Black Woman on TV Today

The most popular reality TV shows featuring Black women are Basketball Wives (2010) and Love & Hip-Hop (2011). Both shows, now huge franchises, were produced and/or created by Black women but have nevertheless been notoriously criticized for their negative portrayal of Black women. This portrayal is especially damaging because it is supposed to be “reality” and not scripted. These shows give off the impression that these Black female characters were not created in some person’s mind, but that they are real and therefore so are the behaviors they display. But the truth is that many of these reality TV characters are just that, characters that either the producers or the actors themselves created. They are often either complete fabrications or exaggerations of reality. However, although the shows may enforce stereotypes, some people do actually behave the way the women on these shows do – whatever their race. Money, the promise of fame, and internalized (or otherwise) misogyny can make just about anyone act a fool on TV. But because most of the characters on these shows are Black women and because of the racist political and social climate we live in, some say we can’t afford to have these images on TV, real or not.

After the inception of the “urban” reality TV show, there weren’t many scripted shows starring a Black woman or a group of Black women. We became sidekicks, co-workers, best friends, or ancillary characters again with barely a storyline or any character depth. Then in 2012 and 2014, producer Shonda Rhimes created two starring roles that anyone of any race could have played but she cast two Black women in them. Olivia and Annalise’s characters on Scandal and How to Get Away with Murder, respectively, are not centered on the fact that these women are Black but being Black is still part of who they are. They are definitely excellent representations of successful, strong Black women with more than a trope amount of character depth and development.

However, some say that Olivia and Annalise’s characters are too excellent, too magical. Olivia and Annalise are not only professional women, but they are powerhouses in their careers. Some find that intimidating and discouraging instead of empowering. I disagree with the negative perception that these two women make us want to live up to impossible standards. Their success is not unachievable and the fact that they are impeccable lawyers who always get the bad guy (or get away from the bad guy) makes them heroic TV characters. After all, these shows were created to entertain us and how entertaining would the shows be if we were always having to root for the underdog who couldn’t escape failure? Also, neither woman is killing the game in their personal relationships. They both are deeply conflicted in their personal lives and this is neither hidden or downplayed. Annalise and Olivia struggle with inner demons and yet push through them to continue achieving their Black Girl Magic.

Even though I disagree with the perception that it is too hard to live up to or relate to Olivia and Annalise’s success and that because of this it is wrong to portray them as so magical, their characters do bring to mind the Strong Black Woman trope. Despite their messy personal lives, they have kick-ass careers. But unlike the Lisa Turtles of the past, Olivia and Annalise acknowledge that the failures in their personal lives do affect them, it just doesn’t stop them from being successful otherwise. The other difference is that Olivia and Annalise are the stars of each of their shows and their characters were created by a Black woman. I think that this outshines any negative tropism. Many Black women in America have the experience that the more successful they become, the less successful they are in their love lives. This is a reality for a lot of Black women and it’s possible that the creator of these shows has written two characters that she herself can relate to. To me, this speaks volumes.

Still, with all that being said, some believe there is still a large gap that needs to be filled with regular, everyday Black women’s stories because both the powerhouse, professional Black woman and the girl-next-door Black woman, and everything in between, are all realities for us. Black women need to see other women on screen who not only look like us but have similar lives as us. We need to be reminded that it is OK to have a degree but no career, to not have a romantic partner, to be a single working mother, to be bored in our relationship, to be sex positive, to be queer or fluid, to be working class and happy, to be sexually inexperienced, and to be perfectly flawed.

Today, as media distributors are realizing that Black millennials are “major consumers of media compared to their market audience counterparts,” more and more shows that are a reflection of us are being produced. Many of the creators, writers, directors, and producers who are now given the chance to make these shows are Black women. The result is a lot more representation; shows and characters made by and for Black women that appeal to the average Black female millennial.

Take the uber-popular show Insecure, for example, which stars its creator, Issa Rae. Her character is the quintessential everyday, regular Black girl. She struggles with her career and her relationship but she isn’t a sob story. She tackles day-to-day issues like workplace microaggressions (and macro-aggressions), a boyfriend who has become complacent in their relationship, temptation from an ex, and just not having it all together, in general. She has a best friend named Molly who low-key represents the successful, strong black woman trope. She is great at her job but she sucks at relationships, although her relationship woes are self-inflicted. Nevertheless, Molly and Issa deal with the ups and downs of life and have another great friendship we as Black women can admire, since our Living Single and Girlfriends days are over. The show also smartly and explicitly deals with race, both in a comical way and in serious ways too.

Chewing Gum, created by and starring Michaela Coel as Tracy, is a show about another ordinary Black girl we can relate to. Tracy’s character is not only flawed and figuring things out, she is so awkwardly and grossly hilarious in ways that usually only white girls are allowed to be (e.g. Broad City). Unlike the oversexualized stereotype of Black women who live in the projects (which Tracy does but in the UK it’s called a council estate) Tracy is a virgin, albeit a very horny one. Throughout the episodes, Tracy deals with her sexuality as well as her super-religious mother and sister and her life on the council estate. Significantly, the latter only serves as a backdrop and doesn’t drive the plot as it might in other shows. She goes through the motions of figuring out her life with the help of her much less naive best friend, Candice, who is that best bud that tells you your ideas are too wacky to take seriously and then helps you to pull them off anyway. Tracy struggles to find her footing in life but she keeps going and making us laugh along the way.

Another great show, Queen Sugar is created and produced by Ava DuVernay and the women who star in this show run the spectrum of Black women characters without being stereotypical. Charley is wealthy and successful but still a sympathetic character who is a mother and a wife. She is a strong Black woman, which is shown through how she survives her relationship difficulties, but not to a fault. She has a breakdown or two throughout her ordeals and makes a poor decision here and there but ultimately she fights through it so that she can be there for her son, her siblings, and most importantly, for herself. Charley’s sister Nova is a freelance journalist, a marijuana entrepreneur, a spiritual healer, an activist, and one of the most well-rounded and interesting characters in the show. She is kind and generous, but also a bit self-righteous. She is sexually fluid and has romantic relationships with both sexes throughout the season, but she doesn’t let these relationships define who she is.

Charley and Nova have a complicated relationship but it is clear they have a lot of love for each other and their brother Ralph Angel. The siblings must come together when they face a tragedy and they do just that, despite their differences. Their Aunt Vi is another strong Black woman and also a little bit sassy. But she treats her family with gentle compassion and ferociously protects them. When she faces her own struggles, she is able to focus on herself and get through it one day at a time.

Darla is a character that evolves throughout the show. She is the mother of her and Ralph Angel’s son, Blue, and a recovering drug addict. Ralph Angel, and especially Aunt Vi, have trust issues with Darla because she lost custody of Blue due to neglect. Despite this, Darla works hard to get well and on her feet and does the best she can at attempting to reestablish a relationship with Blue, Ralph Angel, and his family. All of the characters in Queen Sugar are endearing and represent relatable human beings.

Last, but not least, Van from the show Atlanta is another great example of an ordinary, relatable Black woman, even though the show is not created by a Black woman. No, she doesn’t get as much screen time as her male costars who the show centers around, but she had a breakout episode where she was the main focus. We got to see even more depth to her character and the more we learned, the more we loved her because of how relatable she is. Even though she has a career and a beautiful daughter, she doesn’t have everything figured out. Her child’s father, who is the star of the show, Ern, is an Ivy League school dropout, who if he did not crash at her place, would technically be homeless. Van is a teacher who is one accidentally failed drug test away from being unemployed. On the episode that focused on Van’s character, her friend from high school, who is successful in her own right, comes to visit and she promptly tells Van that she doesn’t know her worth. Van is offended but seems to take what her friend says to heart and the rest of the episode she struggles with who she is and the life she wishes she had.

In a later episode, Van asks Ern to attend an event with her so that she could earn the mentorship of people that could possibly change the trajectory of her career and ultimately give her and their daughter a better life. At the event, Ern and Van must pretend to be married and both have to deal with the implications of this. They also must grapple with the blatant cultural insensitivity and appropriation that runs rampant at the event. By the end of the episode, Ern can’t take it anymore and after blowing up at the host, he leaves and Van is forced to leave too. You get the sense that even though Van may have been willing to endure a bit longer, she was also being pushed to her limit and she felt a sense of relief after Ern stormed out. Although Van’s character is tied to the show through Ern’s character, she is still portrayed with such depth that we feel like we know her because her nuanced feelings are so familiar.

These shows demonstrate that Black women can be magical and yet still flawed. They show full human beings who mess up more than they succeed, women whose sex lives are positive and yet complicated, women who own their bodies and what they decide to do with them, and women who have a lot going for them but haven’t gotten it all figured out yet. These characters get to be normalized, equalized, Black, female, professional, working-class, single, married, divorced, mothers, sisters, and aunts. They get to laugh, cry, make us laugh, and just tell all-around good, relatable stories. They never have to sacrifice themselves for the sake of the show or their male or white counterparts. Best of all they are created by us and created for us, unequivocally. These stories of multi-dimensional and endearingly complicated Black women are the stories of all of us, just with each of our own different layers, and these stories need to continue to be told.

But Can All of Our Stories Be Told?

Black women have been displayed on TV in a plethora of ways over the years. Sometimes with good reception and sometimes with bad reception. Sometimes the intent was there but the execution was lacking. Other times, Black women were shown in a lazy attempt to be more inclusive without putting in the work to do it properly. But no matter how many versions of the Black woman we see on TV, there will always be a Black woman’s story that is not told. This is because we are multi-faceted and we are real. We are at all times both human and magical.

We have seen that the only people we can trust to try to tell the full spectrum of our stories accurately are ourselves. These stories will change over time but one thing remains the same. It is the thing that unites us and that others use to demonize and erase us – the brown hue of our skin that beautifully intersects with the fact that we are women. Though we are part of the same community and our membership in this community creates experiences of oppression and exclusion that need to be heard, we are unique individuals. No one story represents the whole and no story is in and of itself a false representation. So we will continue to crave to see these nuanced stories told in media – not for others to understand us but so that we can be acknowledged and valued for our narratives of humanity like everyone else.

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

– Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Check out Part I of this post, Black TV: “Unrealistic” Black Excellence vs. The “Relatable” Stereotype (Part I – The Black Family)

I absolutely love this!!!! I was just at a lecture at Rutgers University- Camden earlier this year where a guest speaker came in who spoke about a particular tv show that depicted a black female and how she was placed in the scene deliberately and how TV depicted black women in the 60s. It was interesting that the lecturer was a white professor. I wanted to ask her so many questions but I had to leave early for a meeting…

Thanks so much! Yeah, this stuff fascinates me too. I like to make a note of representation in shows, which I guess we all do to some extent, especially now. It’s something we should all pay attention to but remember to take everything for what it is. At the end of the day it’s entertainment but it means so much more – people’s jobs and livelihoods and the opportunity for people to see positive, accurate representation of themselves. And that may mean different things to different people.